curiosity as edgework

reframing innovation in complex systems

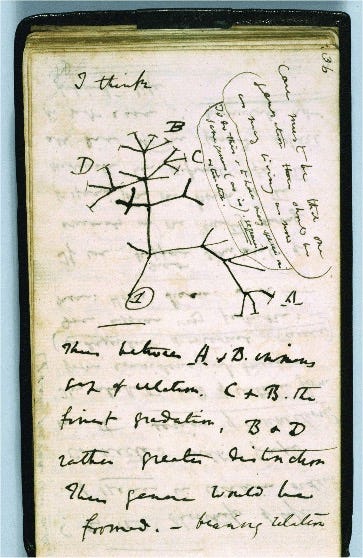

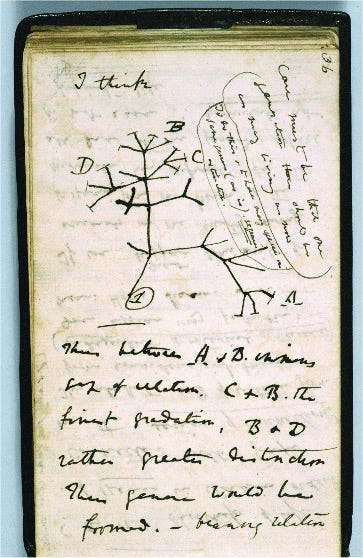

historically, curiosity has been defined primarily as an acquisition enterprise—a drive to fill information gaps, to collect knowledge piece by piece like a magpie gathering shiny objects. yet this framework misses something fundamental about the nature of curiosity: its inherent role as a connective force. rather than merely accumulating isolated facts or experiences, curiosity functions as a form of edgework, creating meaningful linkages between disparate elements in our cognitive landscape.

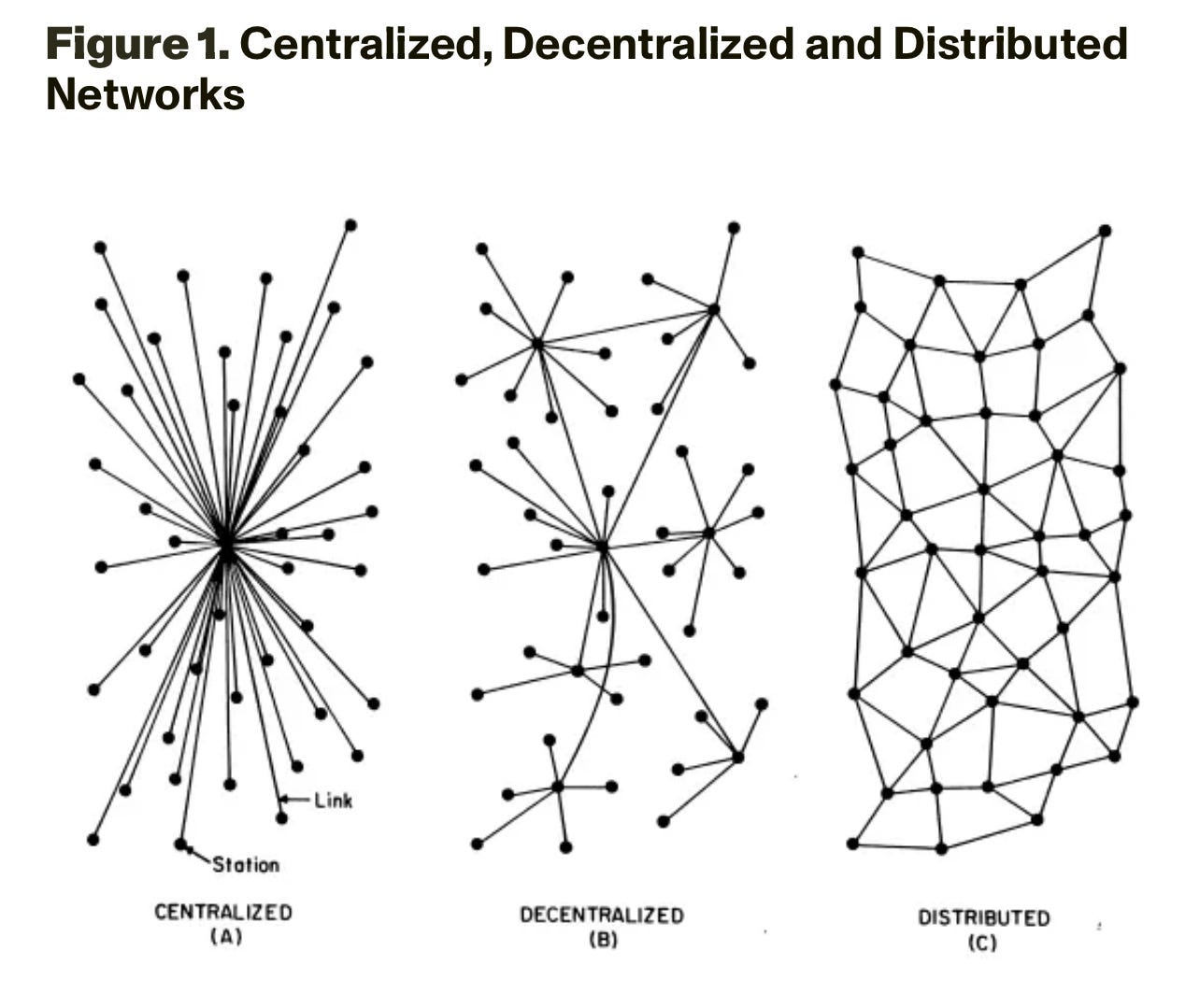

this connective nature of curiosity finds its theoretical parallel in network science, where complex systems are understood through their interconnected nodes and units. the critical insight lies not in the nodes themselves, but in the relationships between them—the edges where different elements meet and interact. when we are curious, we often cannot clearly envision our destination; instead, we operate at these edges, extending tentative connections into unknown territory.

picture knowledge as having invisible tendrils reaching outward into space, searching for potential connections that are not yet manifest. the essence of curiosity lies not in knowing what these tendrils might eventually grasp, but in maintaining focus on the act of reaching itself—in remaining open to unexpected connections and unforeseen possibilities. this is what distinguishes truly innovative thinking from more traditional research paradigms.

contemporary academic structures, however, often work against this natural tendency toward edge-exploration. scholars are typically hired and funded within rigid disciplinary boundaries, limiting their ability to venture into unexplored territories between established fields. the challenge of securing funding for fundamental research is particularly acute when outcomes cannot be predetermined, reflecting a broader systemic bias against open-ended inquiry.

this tension points to a crucial paradox in our collective approach to innovation: while we acknowledge that breakthrough insights often emerge at the intersections between disciplines, our institutional structures continue to privilege research with clearly defined outcomes. the adjacent possible—that shadow future of unexplored connections—remains largely inaccessible within current frameworks.

perhaps what we need is a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize curiosity itself. rather than viewing it as a tool for acquisition, we might better understand it as a practice of edgework—a deliberate exploration of the spaces between established knowledge domains. this reframing suggests that true innovation lies not in the relentless pursuit of predetermined goals, but in nurturing our capacity to work at the edges, where the known meets the unknown and new possibilities emerge.

inspired by dani bassett & perry zurn’s work in curious minds + why greatness cannot be planned: the myth of the objective by ken stanley & joel lehman

https://analoguegroup.org/